Martha Langley had no reason to stop in the village that day. She didn’t need bread, or nails, or anything else to justify the detour. But the wind changed, and something in that change, more a feeling than an idea, made her pull her horse toward the square.

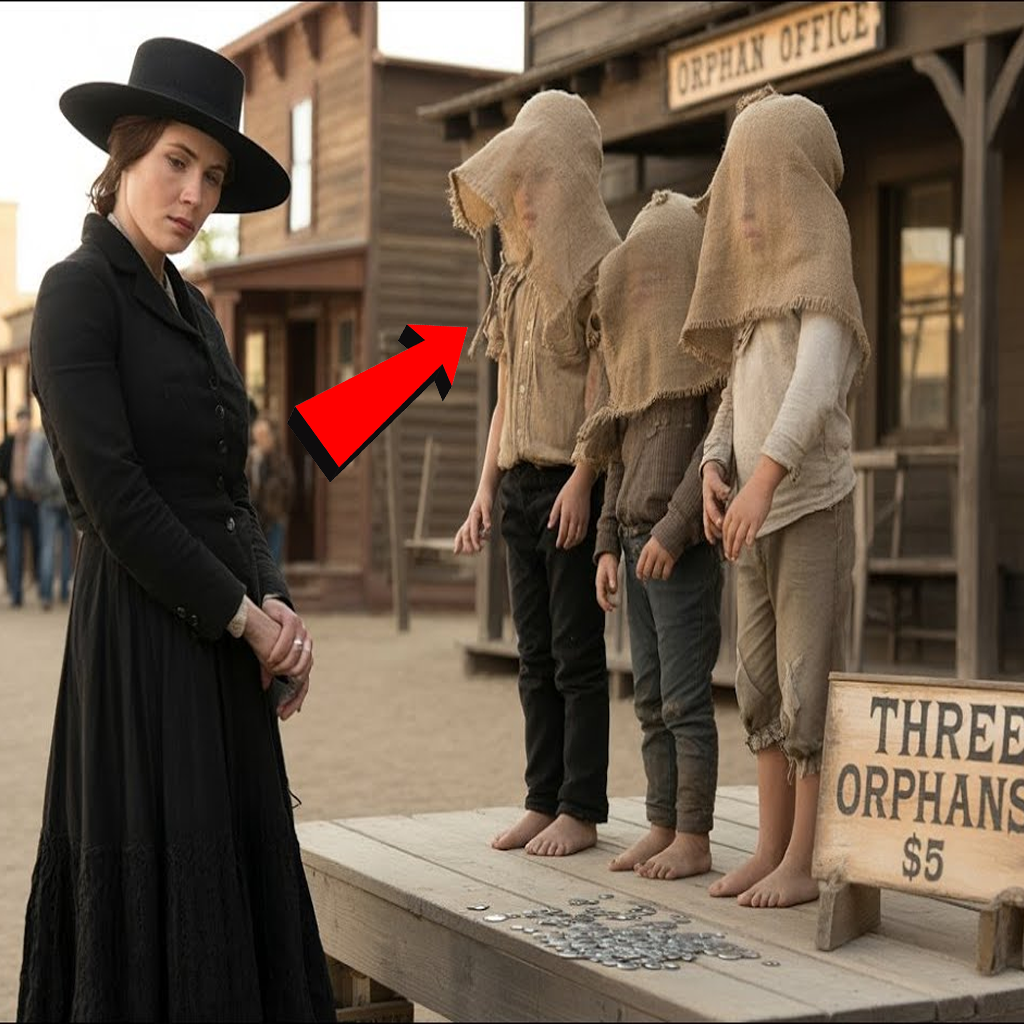

Then she saw three children standing like statues, with sacks tied over their heads and their hands tied behind their backs. At their feet, a hand-painted sign read: “Orphans!” For each one, “No name, no age.” Marta got out of the cart without a word. Her boots hit the ground with the firmness of someone who doesn’t ask permission. At first, no one noticed her.

She was the silent widow who came and went without greeting anyone. But this time she walked straight into the crowd, and something in her eyes made everyone turn around. The auctioneer, a red-faced man wearing short suspenders, coughed uncomfortably. “Ma’am, are you here for one?” She didn’t answer. She just leaned closer. The oldest of the three children, perhaps 11 or 12, swayed slightly but held his ground.

The one in the middle had a black eye. The youngest, barely 6 years old, turned his head toward her. The auctioneer continued speaking nervously. They’re not trained. They don’t talk much. They don’t cry. They haven’t eaten since dawn. Don’t untie them; it could be worse. They might not even talk. I mean, no more. He doesn’t know what he’s buying.

Marta didn’t respond; she just reached into her coat, pulled out her old leather purse, and without hesitation, placed the silver in the auctioneer’s palm. “The three of them,” she said clearly. Silence fell over the square. “Pardon,” the bewildered man repeated. She nodded. “Untie them.” The crowd held its breath.

The auctioneer swallowed, took out a knife, and one by one took the sacks from them. The eldest had pale eyes, steady as ice. The second looked at no one. The youngest, seeing her without the cloth covering her face, murmured with complete certainty, “Mrs. Langley, it wasn’t fear, it wasn’t surprise, it was something more intimate, it was recognition.”

A woman in the crowd murmured, “How do you know her?” But Martha didn’t answer, just put her hand on the shoulder of the little boy, then the middle one, then the oldest, and said, “Come with me.” The auctioneer tried to warn her, “He doesn’t even know your names.” “I don’t need you,” she said, and walked on. They rode in silence.

Martha at the front, the three children in the back of the car, their gaze fixed on the road and their knees pressed to their chests. No one spoke, no one asked where they were going, and she offered no comfort. Not yet, because Martha Langlay knew something many forgot: that when someone has been deeply hurt, offering affection too soon can be a form of violence.

His house was at the edge of the valley, where the pines were tallest and the stream ran cold between the rocks. It wasn’t a beautiful house, and it wasn’t new by any means. The barn was leaning, and the windows hadn’t been cleaned in months. But it was his, and it was still standing. When he arrived, he stopped the wagon in front of the porch. Inside, he said quietly.

The eldest was the first to jump down. He helped the other two out without complaint, without words. They entered like shadows, their steps silent, their eyes fixed on the floor. Inside, the stove still held the warmth of the morning. Marta put the water on to boil.

Then she took out a jar of dried beans, a sack of flour, and began to mix something with firm hands. Sit, she instructed. The children obeyed without speaking. As she stirred the mixture, she watched them out of the corner of her eye. There was something in their postures, in the way they breathed, that told her everything she needed to know. Fear, resistance, alertness. But also a spark of something else, hope perhaps, or something that was just beginning to resemble it.

“What’s your name?” she asked the youngest. He hesitated for a moment, then whispered, “Milo.” She nodded. “And you?” “The one in the middle,” Aris replied without looking up. “And you, the oldest,” she said without blinking. She returned to the pan, pouring the mixture with a spoon as she spoke. “I’m Marta. You said my name, Milo.”

“How did you know?” He shrugged. “I just knew.” “Did someone tell you about me?” “We’ve met before, haven’t we?” “Ma’am.” Martha stopped. “So how?” The boy held her gaze. He was too young to lie, but there was something in his voice that couldn’t be made up. “I heard it while I was sleeping. A lady said it.”

He said, “Martha Langley will come. She’ll take you home.” Milo’s words left the kitchen in a thick silence. Martha didn’t react immediately. Inside her, something had shrunk. Because those words, exactly those, were the ones she had whispered long ago, kneeling alone, in front of her husband’s grave.

That someone needs me again. That someone says my name. Now she had a child who had said it without her asking, and it shook her more than any past tragedy. Bec, the eldest, tensed. “I don’t care how he knew your name,” she said sharply. “But if you’re going to hurt us, do it now. Don’t drag it out.” Marta turned slowly from the stove.

I’m not going to hurt them. Everyone says that. She didn’t argue, just flipped the pancakes. Okay, then I won’t say any more. She served them without ceremony. They ate with the urgency of those who didn’t know if there would be another meal. There was no conversation, just the sound of forks, the crunch of bread, and a tense peace hanging in the air. When they finished, Martha brought out blankets and placed them by the hearth.

You’ll sleep here tonight. There are clean clothes in the trunk. He spoke as if issuing an order, not an invitation. If any of you run, I won’t go after you, he added. But I’ll leave the lamp lit in case you decide to come back. He climbed the stairs, but when he reached the first step, he stopped.

Without turning around, she said, “Tomorrow we’ll talk about what’s next.” That night, no one slept at all. Neither they, nor she, because those words of Milo’s, those of that mysterious night voice, kept repeating in her mind like a prophecy or an answered plea. And at some point, Marta found herself speaking softly, almost unintentionally. Let someone call my name again. Dawn came soundlessly.

The gray clouds still hung heavy over the house, as if the sky itself had spent the night awake. Martha had barely slept, but when the rooster crowed weakly and without enthusiasm, she was already downstairs, dressed and stoking the fire as if it were just another morning. Although she knew it wasn’t. The three boys were still in the same position where she had left them.

Milo curled up by the stove, his thumb pressed against his lip, not quite sucking it. He just held that gesture like someone who needs an anchor to endure the night. Aris, rigid on his back, with his hands crossed on his chest as if waiting to be dragged out. Ibec in a corner, knees to his chest, eyes fixed on the door. He wasn’t sleeping, he was watching her.

Martha prepared warm water and began mixing soap in a basin. She didn’t ask who was hungry. She knew that. She didn’t ask who needed to clean up. That was also evident. She didn’t hug them either. Not yet. She placed a pile of folded shirts next to the stove. Her voice was firm, not tender, but not harsh. They can wash in the barn. They have privacy there.

The towels are in the red box. Bec, you go first. Then Aris. Milo, you last. Don’t come back until you’re clean. For a moment, no one moved. Until Beca clenched her jaw, stood up, grabbed her clean clothes, and left without a word. When Aris followed, Marta was already chopping apples and stirring oatmeal in a pot. She added a sprinkle of cinnamon.

It was an ingredient she’d saved for a special occasion, not knowing why she felt that day had arrived. Milo stood in the doorway, hunched and small. “Can I keep my name?” he asked quietly. She turned. “Why wouldn’t you? Sometimes they change it when they take you in. I won’t.” He looked down in relief. “Because I believe God gave it to me.”

There was a brief silence, one of those weightless ones that only let the soul breathe. “Are you warm enough?” she asked. He nodded. Then, off he went, trotting barefoot toward the barn with something resembling dignity in every step.

The sky was beginning to lighten as the three boys returned from the barn one by one. Beck was last. His hair was still damp. His shirt was too big for him, but it was clean. He didn’t say anything. He didn’t even sit down. He stood by the table as if waiting for orders. “Do you want to chop wood?” Martha asked. “I want to do something that will tire my arms and calm my head,” he replied bluntly.

That changed something. Marta didn’t smile, but nodded with an expression that in another life would have been a caress. She led him outside, showed him the tool shed, the chicken coop, the overgrown vegetable garden, offered no explanations, just pointed, and Bec didn’t ask any questions, just looked, nodded, and got to work.

Meanwhile, Aris was sent to Pilar Leña, and Milo, as if he already knew, followed her around the house, helping her fold blankets, pick up dishes, and line up things no one asked him to. He didn’t talk much, but he didn’t need to. It wasn’t a perfect day. There were long silences, moments when the air filled with tension for no apparent reason. Milo dropped a plate.

Marta raised her voice because of the mud on her boots. Aris didn’t meet her eyes for the rest of the day. And Beck didn’t show up at lunchtime, but when the sun set behind the hill, something had changed in the air. The house, that silent house for years, now had something that couldn’t be bought or built: warmth.

And just then there was a knock at the door. Three sharp knocks, and then nothing. Marta froze. The boys raised their heads. She walked to the door, cautiously opened it, and there stood Reverend Jacob Estoques, tall, thin, wearing a black coat, his hands clasped, as if praying even when he wasn’t speaking. “Good afternoon, Marta,” he said in a low voice.

“I heard in town you made a purchase.” Marta left and closed the door behind her. The reverend stood there, firm but nervous. “I brought them home,” she said bluntly. “I wasn’t sure it was you. Some in town think you’ve lost your mind.” “Maybe I have,” she replied with a calmness that didn’t ask for permission. “But the truth is, they’re not cattle.”

“I know,” he said, lowering his gaze. “But I also know that those boys have been through more homes than a hound. One of them, Beck, broke a man’s nose with a horseshoe and was returned. He won’t break mine,” Martha replied calmly. Reverend Stockes looked at her for a long time, then sighed.

Do you want me to help you officially register them? We can go to the county clerk, make it legal. Marta shook her head. Not yet. First, I need to know they’ll stay. I wouldn’t rely on that, he warned. Not with what they’ve been through. She looked toward the hills, then toward the closed door behind her. Then I’ll make new history, the reverend said.

He let out a faint smile. You were always stubborn. I learned from the best. He tipped his hat and turned to leave, but before mounting, he issued one last warning. Martha, I hope you know what you’re doing. Taking in just one child is difficult enough. Three is a resurrection. She didn’t respond, just watched him go. Inside the house, Milo was spying from behind the curtain.

“Who was it?” she asked in a low voice. “Just someone who worries too much,” Marta said. “He’s afraid of what might happen to us.” “Me too,” Milo replied without looking up. That night, Marta took her old Bible out of the trunk, placed it on the table, and the children watched. They didn’t ask anything. “I used to read this when I was their age,” she said.

Sometimes it helped, sometimes it didn’t. But I thought maybe tonight they’d want to listen. And even though they didn’t say a word, she read anyway. He brings the lonely back to family and frees the captives from their chains. When she closed the book, Milo was already asleep. Aris was wrapped in a blanket.

And Beck, although his eyes were open, was no longer looking at the door, but at her. The night was quiet, too quiet. But the next morning something broke the silence. A barely visible detail, but one that made Marta’s heart pound. There was blood, not much, just a thin reddish thread snaking from the back of the house toward the trees like a careless trail.

The boys were still asleep, or so he thought. He didn’t want to wake them. Not yet. First, he had to know. He followed the trail, crossed the fence, went down the ravine, went deeper into the woods, and there he found him. V kneeling beside a rusty trap, one hand wrapped in a rag and the other outstretched toward a dying rabbit. The animal was trembling, bleeding from its belly. It was barely breathing.

“I didn’t mean to,” Beck murmured without looking at her. “I just wanted to help.” I thought we could have breakfast, but she resisted. She didn’t cry. She didn’t ask for anything, just watched the rabbit, then back at her. “It’s going to die.” Marta nodded. “Yes, I’m sorry.” She bent down, gently picked up the animal, and gave it a quick death. Painlessly, she wrapped it in cloth. Then she looked at the boy’s hand.

You’re going to need stitches. I’ve had worse, he said without drama. But you won’t hear me when, back home, Marta cleaned the wound and stitched it up under the lamplight. Beck didn’t move, just stared straight ahead. Aris and Mimilo sat at the table without speaking, watching in silence. “I want to learn how to catch,” Bec said, suddenly ready to shoot.

For what? So he could protect them. Marta looked into his eyes. There was a maturity there that hurt. “That’s fine, but not today.” He nodded. That night, when he went to bed, he didn’t curl up against the wall like the previous nights. He lay facing the others, watching them, protecting them. And when the children were already asleep, Marta whispered in the darkness.

Thank you. She didn’t say who. She didn’t need to. The scream woke Marta as if a bolt of lightning had struck her soul. It wasn’t a childish wail, it wasn’t a mumbled mama. It was a raw, animal cry ripped from the depths of her body, as if the pain had no way out except like this.

She ran down the hall, her nightgown tangled around her ankles. The door burst open, and there stood Beck, covered in sweat, the sheets knotted around his legs. A hand clawed at the air. His mouth was wide open, but his eyes remained closed. Milo was sitting up in the crib, his hands over his ears.

Aris froze by the window, too scared to move. Beck, Marta said loudly. Nothing. He thrashed about, muttering between broken soyozos. Please, not again. Stop. Marta crossed the room, knelt down, and took him by the shoulders. B. It’s not real. You’re home. You’re safe. His eyes flew open. His whole body tensed as if he’d been plunged into ice. He jumped back.

“Don’t touch me,” she shouted. “It’s Marta,” she said calmly, without moving. “I was dreaming.” Beck looked around as if he didn’t recognize anything. His chest heaved. Sweat trickled down his temples. Milo began to cry silently, that staccato cry you try to hide but can’t. Beck covered his face. “I’m sorry.” He didn’t mean to scare anyone.

“I didn’t want to.” His voice cracked. Then Aris took a step forward. Still pale, but steady. “It happens to him sometimes,” he said in a low voice. “It’s not always this bad, but sometimes it is.” “Should I sleep in the barn?” Beck asked, his voice shaking. “Can I stay quiet? I swear. No one goes to the barn,” Martha answered.

You’ll stay here. Beck slowly lowered his hand. I scared Milo. Milo wiped his eyes with his sleeve and whispered, “It’s okay.” He spit. “I dreamed he was back. The man who bought us before from the last place. I don’t remember his name, only his boots. He always smelled like rope. It’s not him,” Marta said, feeling her throat close up.

“Are you here with us?” She beeped slowly, very slowly this time, and everyone fell silent. Only the wind outside scratching the roof. No one slept again that night. Fear hung in the air like thick smoke from a closed chimney. But Marta did what she knew she should do: not speak, but act. She went down to the kitchen, lit the lantern, and boiled water.

“Let’s make tea,” she said casually. “Tea,” Aris asked. “It helps,” she replied without looking back. “It helps remind us that we’re really here.” The three followed her, silent as shadows. Each chose a cup. Milo, one with blue flowers. Aris, a plain gray one. Bec didn’t choose until Marta offered her a tin cup with a dented rim.

She took it without saying anything. They sat at the table, drinking in silence. Beck’s hands were still shaking, but his breathing was beginning to calm. It was Milo who broke the silence, his voice so soft it was barely audible. Nightmares are like memories. Marta looked at him and answered calmly.

It’s what memories do when you try to forget them too quickly. No one said anything else. But everyone understood. They sat until the sky began to lighten and the rooster’s crow, though faint, sounded less lonely than the day before. Later that morning, Marta took an axe out of the shed. She handed it to Bec.

He looked at her doubtfully. “Do you want me to chop wood? I want you to do something that will tire your arms and calm your head,” he said. “But don’t touch that pile without me showing you how. If you chip that knife, I’ll have you sharpening it until Easter.” Bec nodded. For the first time, she almost smiled. And so, as the sun rose, something else began to rise in that house, a sense of direction. Beck had strength, but not technique.

He’d had knives, ropes, even whips, but never a tool given with purpose, much less instruction. Marta corrected his grip. She taught him the difference between splitting a log and cracking a knuckle. It wasn’t the kind of instruction one gave with affection. It was firm, practical, but with purpose.

And Beck absorbed it all as if she’d been waiting for years for someone to explain it to her, without yelling, without chastisement. By midday, she was already sweating. The woodpile was growing, and her thoughts, at least for a while, were calming. Ari, meanwhile, helped her in the garden. She didn’t say much, but she had an instinctive gentleness. She touched the earth as if it might break.

He returned the worms to the ground carefully, not with fear, with respect. “Did you ever have a family?” he asked suddenly. Marta stopped. She looked at him. “I had one. And now, gone.” He didn’t ask any more questions, just nodded, as if learning how much loss a person can carry without breaking. Milo, for his part, swept of his own volition, not because he was asked.

He liked to make lines in the ground. As he did so, he murmured old songs without complete lyrics, only fragments, forgotten hymns. This little light of mine whispered over and over again, unaware that Marta was listening. That afternoon, while baking bread, Marta found herself humming the same tune.

Three days passed, then four. Then a week later, the children began to change, though none of them noticed, and neither did she say so. But the change had already settled into every corner of the house. Something had begun to blossom in that house, though no one mentioned it. Aris began to read aloud by the fire. It wasn’t good.

He stumbled over long words, but Milo always clapped anyway. Beck didn’t ask for chores anymore; he just did them. Martha discovered him one afternoon repairing the barn hinge with a bent nail. “Who taught you that?” she asked. He shrugged. “You did that when you fixed the door latch.” Milo, for his part, began leaving little drawings under Martha’s pillow.

Clumsy crayon strokes, sometimes unrecognizable, but there was always a figure that represented her. There was always a word written in some corner, home, but not everything was perfect. One night, Aris returned with a black eye. Marta noticed it immediately. What happened? Nothing, he said. Don’t lie to me. Aris looked down. The kids in town call us trash.

They insulted him. I told them to stop. They didn’t. Ib stood still. He didn’t respond. And why didn’t you run? We’re not running anymore. Marta bent down and lifted her chin. You’re brave, she said softly. And stupid, too. It’s the same. Sometimes it is. That night she cooked a hot stew and sat them all down near the fire. Closer than ever.

Beck didn’t say much, but gave Aris an extra slice of bread when he thought no one was looking. The next morning a letter arrived. It had the county stamp on it. Martha read it twice, then folded it and put it in her apron pocket. After breakfast, she reunited with him.

“They’re asking us to go to the city,” he said. “Silence.” “Why?” Beck asked. “Do you want to ask questions? See if I’m up to it. If you’re okay.” Milo spoke firmly. “We don’t want to go.” “You don’t have to stay,” Marta replied. “But you must come with me. You must show them what we’ve built here.” Beck stood up.

And if they try to take us, then we’ll show them who they really are, she said, not what others said, not what was done to them, but what they’ve become. The ride to the city was long and silent. No one spoke. But the tension was felt in every held breath, in every averted glance.

When they arrived at the Palace of Justice, Marta pressed her lips together. The building was red brick, imposing. It smelled of ink, varnish, and distrust. An employee greeted him with a stern look. Marta stood her ground. So did the boys. Milo took Beck’s hand. Aris didn’t flinch for a second. The interrogation was cold, mechanical.

They sleep through the night, they eat three times a day, do they feel safe? One by one, the boys answered, “Yes, yes, yes.” Beck’s voice cracked once, but he repeated the word more forcefully. Yes. The clerk leaned back in his chair as if unsure what to make of such certainty. “You’re lucky, Mrs. Langley,” he said, “more for yourself than for them. They could have rotted out there.”

“Not many people would accept three children, especially with that kind of background.” Bec interrupted him without raising her voice. “She didn’t accept us. We chose her.” The silence was total. The man blinked, not knowing how to respond. When they returned home that night, Marta found something under her pillow.

A drawing, four stick figures holding hands in front of a crooked little house with smoke rising from the chimney. And a word written in capital letters, found. For the first time since she buried her husband. Marta cried. Not silently, not in secret. She sat at the table and let the tears fall. The children didn’t ask why, they just stayed with her, and that was enough. The first snow came early.

It fell silently, like delicate lace spreading over the hills. By morning, the landscape had disappeared under a white blanket. The sky was gray, heavy, as if it, too, had retreated to rest. Marta watched from the porch, her shawl wrapped around her body, her breath rising in puffs.

Inside, the boys huddled around the stove, sharing a single wool blanket as if it were a treasure. “Is that snow?” Milo asked, pressing his nose to the glass. “It is,” Beck replied, still staring at the fire. “I can touch it all I want, but if you go out without boots, your toes are going to snap like twigs.”

Milo burst out laughing, though he couldn’t tell if Beck was serious or not. Breakfast, Martha called from the kitchen. Warm biscuits, but only if someone sets the table first. Beck stretched out his arms. Always me, like a good older brother. Milo ran to his post, still staring out the window, trying to catch every snowflake.

They ate in a silence that was no longer awkward. It was a silence filled with things unspoken, but felt. A silence of understanding, of warmth, of family. Marta watched them for longer than she’d intended. “Why are you looking at us like that?” Bet asked, a cookie halfway to her mouth. “Because I’m proud,” she replied in a barely whispered voice. The three of them stopped.

It was Milo who reached out and took her hand. He didn’t say anything, he just held it, and that gesture was worth more than any words. That afternoon, Milo was the one who insisted. “We have to make one,” he said determinedly, wearing his gloves inside out. “One what?” Aris asked. “A snowman.” “I’ve never made one.” No one objected. No one said it, but everyone needed one.

They emerged wrapped in cloaks, sliding on the ice like children who had never experienced a real winter. Milo oversaw the construction with an architect’s seriousness. “He needs arms,” he said, surrounding the plump doll. And a hat. “Give him yours,” Beck joked. “Don’t even think about it. My ears will freeze if I take it off. You were the one who said we should build it. I never said I needed to hear.” He burst out laughing.

A real laugh, free and deep. Aris came out with two branches and a tin lid for his head. From the porch, Marta watched them with a cup of hot tea in her hands. She didn’t move, didn’t speak, just listened to the crunch of boots in the snow and the laughter.

It was the kind of music you don’t find on any record. It had been too long since she’d heard children laughing in that yard, since her husband laughed with them, since she’d allowed herself to imagine that sound could return. But it was there, and it wasn’t nostalgia; it was present. When the sun fell behind the hills, the sky burned in shades of gold and violet.

The boys returned soaked, their faces red from the cold, but radiant. Marta made a stew. They hung their wet clothes by the fire. Steam rose from their boots, hats, and gloves. Milo wrapped himself in one of his old shawls. Beck took out a deck of cards. “Who wants to lose tonight? You always cheat,” Aris replied.

You always lose, Beck countered. One thing doesn’t negate the other, Aris said with a grimace. They played three games, then simply fell asleep right there on the floor, curled up in a ball with their arms and legs tangled together. Marta didn’t move them, just covered the small pile of bodies with another blanket and sat there by the stove until the embers died down and silence returned, but this time it didn’t hurt. Five days later, the problem came.

Martha had gone to town alone. Supplies were scarce, and the boys were busy repairing the chicken coop that a raccoon had destroyed the night before. It was supposed to be a quick visit, but as soon as she walked through the door of the general store, she sensed it. Something was wrong. The man behind the counter, Geralwas, stopped stacking sacks of flour and lowered his voice.

Marta, someone came asking for the boys. She stopped dead in her tracks. What kind of questions? The ones you wouldn’t want strangers asking. He said he had papers. He said he was related. Marta’s stomach knotted. He said his name. No, and no one had time to stop him.

He rode east toward your property. Marta didn’t wait. She left the supplies unpacked. She mounted her horse as if she were 20 years younger. She galloped with an urgency that ached her bones. Snow and sleet flecked her coat, but she didn’t slow down. Her heart pounded as loudly as the animal’s hooves. And as she reached the last hill, she saw him.

A dark horse was tied up in front of his house. Heavy saddlebags, open doors. He jumped off the horse’s back before it could stop. He ran. Inside. The three boys were lined up like soldiers. Backs straight. Staring straight ahead. Stiff. In front of them. A tall, pale man in a long coat and with a neatly trimmed mustache like a villain in a pulp novel. In one hand, a folder.

In the other, something much worse. A child’s dress like the ones they’d been wearing when she found them. “Stay away from them,” Marta shouted. The man turned slowly. “You must be the widow,” he said with a crooked smile. “You’re not lost. No, I came to get what’s mine.” He opened the folder. Transfer documents signed by Judge Hammón.

Two counties south. Legal. You paid for meat, not family. He gave a dry laugh. What a lovely word for stolen property. Be took a step forward. Say that again, he said in a low but shaky voice. And I’ll knock your teeth out. The man laughed harder. You think you can fight me, brat? I already did, mutt.

The man snapped. You and your little brothers. Aris stood next to Beck. Then we bite, Milo said. He pressed himself against Marta’s leg. The man reached into his coat, but Marta was faster. She already had the rifle in her hands and didn’t hesitate to aim it. Try it. The man froze. Do you think you’ll shoot? I’m scared. And that means I might.

He slowly withdrew his hand. “You’ll pay for this. I already did it,” she replied, “and yet they left them for me.” The man backed off, mounted his horse, and disappeared. Marta didn’t lower her rifle until the sound of hooves had completely faded. That night, no one slept. The fire burned low, but it wasn’t warm enough. Milo shivered, clutching a blanket.

Beck held the rifle in his lap, his jaw clenched. Aris kept glancing out the window as if he expected the man to reappear at any moment. “He’ll be back,” Beck said bluntly. Marta nodded. Maybe, “but we’ll be ready to fight.” She looked at him. No, to stay together. Aris clenched his fists. He thinks we’re weak.

Well, let him think about it, Marta replied. It’s easier to surprise them that way. Beck let out a dry laugh. Not mockingly, but strategically. The next morning, Marta saddled the horse. This time she didn’t go alone. The three boys accompanied her to the courthouse. They crossed the city without lowering their heads. They entered Judge Tamlin’s office.

Marta left the forged documents on the desk. “I didn’t sign these,” said the judge, adjusting his glasses. Judge Hamonde is retired; he hasn’t signed anything in years. So, someone is falsifying papers to kidnap children. The judge paled. “We’ll take care of it. You have my word.” Marta looked at him without flinching. “I don’t want promises, I want names, and I want peace.”

The judge nodded with the seriousness of someone who fully understood what was at stake. When they left, Marta put her arm around Milo. The boy said nothing, just rested his head against her side. That winter the snow continued to fall, but the house no longer felt fragile.

The days were short, the nights long, but filled with a peaceful routine that gave them something they’d never had before: Rhythm, security, warmth. He started baking. Aris devoured all the books in the loft, then reread them, and Milo wrote his first word. It wasn’t the dog, it wasn’t the bread, it was Marta. He left it written in chalk on the wall by the hearth.

When she saw her, she didn’t cry loudly, just enough to show it was real. When spring came, the garden was alive. The boys too. Each at their own pace had begun to grow with the soil. The rosebushes arched like delicate seams in the fertile earth. Marta moved among them with her sleeves rolled up, humming softly.

It was a song without lyrics, but with hope. Milo walked behind her, carrying a basket bigger than him. “Can we cook everything today?” he asked breathlessly. “Do you want cabbage stew again?” Beck’s birthday is coming up, and we should do something special. It’s two weeks away, so we have time to get it perfect.

Marta smiled, not at the joke, but because they were starting to think about the future, and that was new. Beck and Aris worked in the shed as if they’d been born there. They hammered, carried wood, straightened nails. They no longer looked like children with sacks on their heads. Bec had grown several inches since winter.

His sleeves were too short, and Aris’s voice no longer sounded childlike. The house had changed, too. More light, more order, and more sounds: laughter, footsteps, murmured conversations. But peace, as always in the West, had an expiration date. And the first warning arrived unsigned, a piece of parchment without an envelope slipped under the door.

One night, Marta found him at dawn as he was leaving, holding the lamp. The calligraphy was elegant, but the words were like a knife. You stole them. This isn’t forgotten. She didn’t tell the boys; she just burned it in the fireplace. But the past had returned to sniff at the door.

The second warning wasn’t a letter, it was a missing chicken, then a dead goat, its neck broken, no sign of a struggle. Beck was the one who found it, and he was the one who buried it before Milo could see it. It was wolves, Aris said. Beck denied it. Wolves don’t kill to leave the body intact. This was a message.

Marta didn’t argue; she just started locking the door and sleeping with the loaded rifle next to the bed. Beck’s birthday arrived under heavy clouds, a storm, and thunder that rattled the windows. But inside the house, they lit every candle they could find and laughed. Milo carved a wooden whistle for him. Aris gave him a hand-sewn bag to carry tools. Marta gave him a coat, a special one.

It had belonged to her husband, dark, made of thick wool. It still retained the faint scent of tobacco and the sun of winters past. Beck received it in silence. “I can’t wear this,” he murmured without looking her in the eye. “You’re already doing it,” Martha replied. The next morning he put it on without a word. And that very day everything changed.

Just before noon, Milo pressed his nose to the kitchen window. Dog. Marta approached through the mist. A stray dog, with prominent ribs and yellow eyes, was watching them from the grove. “Not a good sign,” Marta murmured. Be was already outside. “Come back,” Marta shouted from the window, but he shook his head. “I just want to see.”

Then the dog started running, not toward the house, but into the woods. And just as he disappeared, the echo of a shot was heard. One. Then silence. Then three more. Beck fell to the ground. Aris pulled Milo out of the window in a second. Marta froze. Not for lack of courage, but because her body already recognized that rhythm.

One shot to warn, one to wound, two more to show it wasn’t a mistake. She knew what it meant. They were watching her, and now they were getting closer. They didn’t sleep that night. Marta forced the children to stay in the kitchen, away from the windows. They ate cold bread and beans. Beck, jaw clenched, never let go of the rifle.

His eyes darted from corner to corner, as if they could see danger before it appeared. He wasn’t the same boy anymore. He had grown, but that night he looked even older than he should have been at his age. “Do you think they’ll come at night?” Aris asked. “No,” Marta replied. “Cowards don’t walk in the shadows; they wait for the light, and they waited. The next morning brought fog, nothing more. But the fear remained anchored in the walls.

Two days passed, then three. Food was starting to run short. “I can go to town,” Bec finally said. “I’m faster.” “You’re a boy,” Marta replied. “If they see you, they’ll ask for you. They already know who you are.” He didn’t argue, just took the long way around. He avoided the highway. Three hours there, three hours back. When he returned, he was pale. “What happened?” Aris asked.

“There’s a new man in town,” Beck replied. “He keeps asking for me, asking if Marta lives alone. Did you say anything to anyone?” There was no need. The sheriff had already noticed, but he’s not alone. That night Marta unpacked a box she hadn’t had since her husband died. Inside was a revolver, a box of ammunition, and a map. She spread it out on the table. “There’s a safe place.”

Three valleys further. A farm run by the church. They help families. If I go out tonight, can I arrive before dawn and talk to the pastor? Are you going alone? Aris asked. Someone has to stay and protect the house if I don’t return. We won’t leave, Beck said firmly. And that’s what worries me most, she said. In the end, Marta left at dusk.

He rode with his revolver strapped to his side, a bag of dry bread and salted meat in his saddlebag, and the hope of returning before anything went wrong. But danger didn’t wait. At dawn, still at midday, he heard the thunder of hooves. A different kind of storm, not of rain, but of men. He tried to divert his horse across a narrow stream, but they were faster.

In less than an hour, she was surrounded. Three horsemen, their faces covered, weapons drawn. The one in front approached, circling like a vulture. “Where are you going, miss?” he asked mockingly. “To the church,” Martha replied. “It’s none of your business.” “No, but those three children you’re sheltering are,” he replied.

They left them like trash. I picked them up. I gave them a home. You stole it from someone who paid well for them. So maybe the system is broken. Maybe, he said, laughing. But that doesn’t change the law. So maybe the law is broken, too. He narrowed his eyes. You’re brave to be alone.

“I have enough lead to go around,” Marta said, raising her revolver. “And I have friends,” he said, whistling. Four more men came out of the woods. She didn’t lower her weapon, nor did she fire. Instead, she dismounted. “If you’re going to take me, you’ll have to drag me. I won’t walk with men like you.” “It won’t be necessary,” the leader said, and hit her.

Meanwhile, back at the cabin, the boys waited for a day, two, three. Bec couldn’t take it anymore. She wouldn’t leave us, she said. Maybe she got stuck or hurt, Aris tried to say. Beck shook his head. Something happened. He opened the box Marta had left, the second revolver. The map. Handwritten names. We’re going to get her, Beck said. We can’t leave the house, Aris said.

Milo, who had been silent this whole time, looked up. “I’m going.” “You’re not strong enough,” Beck replied. “I don’t care. She’s my mom, and that stopped them all.” No one had said that word until then, but he didn’t need to explain himself. The next morning they packed the essentials and set off.

The road was tough, but no tougher than what they’d already experienced. They followed the route Marta had traced on the map. Every curve, every twisted tree, searching for traces, searching for something that would tell them, “She was here.” At noon, they found her. Not Marta, but the horse with a gunshot wound to the chest. Deck fell to his knees. The animal was still warm, but there was no sign of her.

Only a barely visible trail of blood leading eastward, toward the hills, away from the village, away from the church, toward where men took those they didn’t want found. Beck stood, his eyes blazing. We’re going to bring her back. He said it like a promise. They moved before dawn the next day.

They walked through the fog, using the trees as cover. Beck carried the rolled-up map under his arm. His revolver was holstered at his side. He didn’t look like a child; he looked like someone on a mission. Aris trailed behind, listening for every creak of a branch. Milo walked between them, his fists clenched, a wooden sling hanging from his neck. He hadn’t spoken since they found the horse, but he hadn’t cried either.

He only said one thing: she’s alive. And no one dared contradict him because believing otherwise wasn’t an option. The hills were cruel. The brambles dug into their legs. The air grew thinner with each step, but then Aris saw the first footprint. Small, narrow, with a slight drag, as if the person leaving it was walking with difficulty. It’s a woman’s, he said.

Beck. He bent down, ran his fingers over the mark, his lips moving. He said nothing aloud. Maybe it was a prayer or a memory. We’re close, he whispered. And it wasn’t hope, it was certainty. They found her by accident. They were crossing a narrow passage between rocks when Milo stopped dead in his tracks and tugged at Beck’s sleeve. There he whispered.

Beyond the trees, among the damp undergrowth and moss, stood a rickety, old shack, leaning, as if the mountain had grown tired of supporting it. Smoke rose from the chimney, not much, but enough to let me know someone was inside. A torn red scarf hung on the porch. “It’s hers,” Milo said firmly.

It could be a trap, Aris warned. We can’t wait, Beck replied. We entered silently, quickly, without error. They approached, crouching low. The porch planks creaked under Beck’s boots, but he didn’t stop. He signaled Milo to stay back. Aris drew his knife. The door was ajar. Beck pressed his ear to the frame.

Silence. He pushed. Light entered the cabin, and the first thing they smelled was dried blood, sweat, and fear. A broken chair, a frayed rope on the floor, an overturned table. “There,” Aris whispered, pointing to a corner. “She was tied to the bedpost.” Marta, her wrists red, her dress torn, a purplish bruise under her cheekbone, but her eyes open, alive, fixed on them.

And when she saw them, she didn’t scream, she didn’t cry, she just smiled. She knew they would come. Beck ran. He cut the ropes, his hands shaking. “Did they hurt you?” “Not the way they wanted,” she said, her voice raspy, but unharmed. Aris ran to the window. “There’s no sign of them. Maybe they’ll come back,” Marta interrupted. “They just went out for supplies.”

Who? They’re not just looking for me, they’re looking for the boys, a new buyer. They say orphans like you are worth twice as much if you’re used to them. Then Milo’s voice came from the doorway. They’re coming. He stood there, stone in hand, eyes wide open. Three men were coming up the path. Beck helped Marta to her feet.

Can you run? No, but I can lean on you. Then let’s go. The back door opened onto a ravine, steep, slippery, covered with mossy stones. There was no time to hesitate. Beck went first, holding Marta with one arm, helping her down as she stumbled. Aris came down behind, covering them. Milo was last, and they hadn’t even gone halfway when a shout erupted from the hill. There, there they go.

The shots didn’t take long. Three quattros, the echo of hooves. Bullets breaking branches, splintering bark, biting into the ground at their feet. Aris turned, aimed Marta’s revolver, and fired once. One of the men fell. The others scattered, but not for long. “They’ll surround us,” Beck said.

“We won’t get out if we don’t buy ourselves time.” Marta gritted her teeth. “There’s an abandoned mine less than a kilometer away. My husband used to hunt near there. If it’s still standing, it can give us cover.” “Then let’s go,” Beck replied. They ran, Marta leaning on him, getting heavier with each step. Mi slipped twice, but Aris picked him up without stopping.

The mine entrance appeared between the trees like the mouth of a sleeping beast, half-collapsed, gaping dark. Beck didn’t hesitate. They entered. The flashlight hung from his belt. The light barely touched the rusty rails on the ground. An old cart, overturned, the air damp and thick. “Deeper,” Beck ordered. “We’ll look for a hole to hide in.” Milo clung to Aris’s shirt.

And if it collapses. Then we risk that because it’s worse out there. They didn’t take long to hear them. Boots, echoes, labored breathing. “I told you they were coming down here,” one of the men muttered. “They won’t get far. This cave is their coffin.” Beck hid around a bend. He passed the revolver to Marta. She looked at him, her hands trembling.

If they get too close, shoot without question. He disappeared into the darkness. He waited. He held his breath. The first one passed. Beck hit him with a piece of rusty rail. He fell without a sound. The second spun around screaming, but Aris charged at him, knife ready. The third raised his pistol but missed. Marta did it first.

The shot echoed like an explosion in a mine. She lowered the gun. She was shaking. “I didn’t think I would do it, but you did,” Beck said, taking the gun carefully. “You saved us. We’re still not safe.” And she was right. The fourth man was still breathing. The fourth man wasn’t dead, just wounded.

He was bleeding from his cheek, trying to drag himself along the ground, his hand reaching for his fallen gun. “Please,” he gasped. “I didn’t sell them out, I was just following orders.” Beck looked at him. Then he looked at Marta. She bent down. She calmly picked up the gun from the ground. “Tell them who sent you,” she said, her voice low but firm. “If they come near my boys again, I’ll shoot the next one between the eyes.”

He stood up, returned the revolver to his belt, and turned away. “Leave it.” “Really?” Aris asked. “Yes, let him walk back, tell what he saw, and let him know that we had compassion once.” They left the mine through a side shaft Beck remembered from the map.

It took them twice as long to round the ridge, but by dusk they had left the blood, the smoke, and the cabin behind. By the next dawn they were back home. No one spoke, only their packs. Milo lay down on the rug without even taking off his shoes. Aris sat in silence. Beck stood, staring out the window as if expecting to see another horse with dark saddlebags.

And Marta just breathed. Weeks passed before anyone mentioned what had happened. But one night, while they were drying the dishes, Milo approached Marta. “Do you think they’ll come back?” She paused. She didn’t respond immediately. “Maybe,” she said finally, “but we’re stronger now, and they were.” Beck built a second fence. Aris set traps.

Martha adopted a huge, silent bloodhound that slept under her bed and patrolled the porch like a sentry. The fear didn’t go away, but it no longer ruled them. They planted a tree where the mine had been. Small, spindly, but vibrant. It didn’t bloom until spring, and when it did, it was Milo who noticed.

He ran in with his face covered in mud. “It has flowers!” He screamed, “it’s really white.” Marta dropped the cake tin she was drying. She ran after it to the edge of the field. There stood the tender, brave tree, blooming. And in silence, everyone knew they had survived.

Beck knelt beside the tree and brushed a white petal between his rough fingers. “I told you it would grow,” he said. “You didn’t say it would die with the first frost,” Aris replied from behind. “Street.” Marta laughed, and it wasn’t a laugh of duty. It was one of those that frees the chest, that sweeps away the remnants of winter within. The boys were healing too, but not just from the bruises and hunger.

They were healing from the silence, from abandonment, from not having been wanted, although even peace comes at a price. That night, someone knocked on the door. It wasn’t a timid knock. There were three firm knocks. Then, silence. Beck was the first to rise, his hand on his revolver. Aris peeked around the curtain. Only a rider.

The horse was exhausted. Marta stepped forward. Leave it to me. Her voice was calm. It was no longer the same woman who had once bought three children for nothing. It was different. Louder, clearer. She opened the door, and it wasn’t a man, it was a boy barely older than Bec, with a hat that was too big and boots worn to the bone, his eyes red, his back bent.

She held a crumpled telegram in her hand. “Are you Marth Bone?” she asked, her voice shaking. “It’s me,” she said. She handed him the paper. “It came urgently.” It said that if she didn’t ride straight, the children would die. Martha felt the ground shake. She unfolded the message with tense hands. “Three children kidnapped. Wagon heading south. Auction in progress. Need help.”

C. He didn’t need more. He didn’t ask who C was. He knew perfectly well who. One of those who once managed to escape. One of those who promised not to forget the others. I’ll ride, Beck said, tying his boots. No, Marta said. I’ll do it. The room froze. I’m not asking your permission, he added. I’m telling you.

“I’ve spent years trying to build a home for kids who never knew what it felt like,” he said firmly. “And if there are others out there, I’m not going to wait for another grave to remember them.” He turned to Aris. He saddled the horses. We left in an hour, and no one argued. By dawn, they were crossing the ridge. The rain bit at their shoulders like an animal tired of warning, but they didn’t stop.

Marta led the way, Bequiaris followed, each with a silent conviction in their eyes. The river was swollen from the storms, but they knew where to cross. A shallow bend, where the red rocks looked like warning marks. On the other side, Marta dismounted. She knelt, touched the ground.

Four heavy wheels. They’re going in a hurry, he muttered. They can’t have been more than a day ahead. They moved on. The landscape changed. The trees turned to dust, the roads harder, the air thicker. At dusk, they came to a trading post with boarded-up windows. The smell of blood, broken glass. A man was silently sweeping.

Marta approached. Three children passed by here tied up. One was limping. The man looked up. His eyes were hard. And why should I tell you? Aris stepped forward. Because if you don’t, she’ll ask again. And then I will. The man hesitated. Then he pointed south. They broke the wagon’s axle. They repaired it here.

They said they were heading for the porter’s mill. Martha tensed. Private auction. What did you say? Beck asked. An auction where no one shouts, but everyone pays dearly. They didn’t sleep that night. They rode under the moon as if the darkness were their ally. When they reached the edge of the valley, the sun hadn’t yet risen, but fires were already burning below.

Dozens of tents, armed men, and in the center, a corral of stacked boxes and barbed wire. Three small boys. One clutched his stomach, another had a sack still tied around his neck. Marta didn’t cry, she just exhaled. “Lend, firm.” “We went in silently,” she said. “No,” Aris replied, opening his coat.

He had dynamite. Beck looked at him incredulously. “You’ve been carrying that?” “Just for a just cause,” Aris said. “And it is.” They waited until midnight. Marta was the first to move. She descended with the calmness of someone who no longer asks permission. She walked toward the crates as if she were part of the place, as if she belonged there. And no one stopped her.

The children saw her and blinked. One reached out, she brought it to her lips, then cut the wire. Ari lit the fuse. Beck mounted the horse. The explosion shook the tents. The guards ran. There was total confusion. And in that instant, Marta pulled the children out.

They ran, they rode, they didn’t look back, and when dawn broke, they were home. The three rescued children slept cuddled up in the living room. Marta’s dog, which had barely wagged its tail before, now refused to leave their side. And although no one said anything, everyone knew. Something had changed. Weeks passed before anyone brought up the subject again, until C arrived.

He rode a mule with a hat so wide it covered half his face, but his smile was unmistakable. “Did you get my message?” he said. “I got it,” Marta replied without even letting him in. C took a worn notebook out of his coat. He laid it on the table. Names, ages, destinations. Marta scanned it. Each line a story that wasn’t yet finished. Children like Beck, Aris, Milo.

Children who were still trapped. There are more, C said. Too many. Marta didn’t look away. So we continue. You, the boys, and anyone who wants to help. C. Felt. Welcome to the fight. That night Beck sat on the porch with the flashlight off, but in his lap. Milo fell asleep, leaning against the dog.

Aris, sharpening wood, was carving something for one of the new children. Marta came out carrying Jonas, one of the new arrivals, in her arms. The boy looked up. They are my new family. Marta didn’t hesitate. We are the real family. And in the distance, lightning flashed across the hills, but no one flinched. For the first time, they weren’t afraid of the storm, because now they knew who they were.

The storm arrived with a low growl just after midnight. It wasn’t a blast, it was a long whisper, as if the sky had also been waiting for this moment. The rain didn’t fall all at once. It slid slowly, wetting the windows like an old voice returning home.

And most incredibly, no one woke up. Not even Milo, who had previously been disturbed by the slightest creak in the ceiling, was now fast asleep, curled up next to the dog. Beck was snoring softly, a book still open on his lap. Aris had fallen asleep standing in the doorway, knife in hand, and Marta, sitting by the fireplace, a cup of cold coffee in her hands, stared into the fire without thinking, without waiting.

Just feeling, the cabin was no longer just theirs; now it was filled with footsteps, laughter, and life. At the back, in one of the rooms, the youngest members slept: Jonas, Paulie, and Benen. The latter still cried in his sleep sometimes, though he tried to hide it, but that same night, before falling asleep, he had given Marta a crumpled piece of paper with a single word written in charcoal, in crooked letters: Mom.

No one had asked her, no one had told her how to spell it, but somehow she knew. Marta kept it folded in her apron. Close to her heart. They’re recovering, she whispered to the fire. Aris, half asleep, nodded from the doorway. So were we. Outside, the wind changed. It carried the scent of mud and wildflowers. Two signs Marta knew well.

Spring had arrived again, and this time the house was ready to welcome it. Days passed, and the house was no longer silent. Now it bustled with footsteps, games, and voices singing out of tune, but from the heart. Be taught the little ones how to fish, though Milo swore the worms made him gag. He carved wooden toys.

She said they were just to keep her hands busy, but each smooth edge spoke of affection. Martha planted. She added more roses to the garden. She said more flowers meant more things to linger over. Jonas helped her, not out of love for gardening, but because he liked being around her.

Sometimes she would ask without asking, “Do you think I’ll grow taller? Do you think this is my family?” Marta never doubted it. It already is. One afternoon Beck received a letter. He read it twice. “Are you going to say yes?” Aris asked. Marta looked out the window. The children were running among fireflies and damp earth.

Laughter mingled with the creaking of the wooden floor. She didn’t respond with words, but the answer was in every corner of that house. Yes, she had already said yes. The years passed, and the tree they had planted next to the mine grew tall and firm, covered with new leaves every spring. Under its shade, they placed a small sign.

She didn’t mention names; she only spoke for those who never made it and for those who did. And the house also grew with more rooms, more blankets, more children. Some arrived bruised, others silent, but none stayed that way for long, because Marta never closed her door to anyone. And over time, the town began to call her by another name. She was no longer just the Widow Langley. They called the house the Light of Blessing.

The light of blessing. That’s what they called it. But for the children who lived there, it wasn’t a symbol; it was their home. There, no one asked where you came from, only if you wanted to stay. And although the world outside remained just as harsh, life in that corner was different.

One afternoon, Martha was standing in the garden, her hands covered in dirt, when Jonas, now taller and stronger, called to her from the porch. “There’s another one,” he shouted. “Another one has arrived.” She wiped her hands on her apron as always and walked with that mixture of calm and haste known only to mothers who never asked to be one, but who are. The new baby was standing by the door.

Skinny, with big eyes, an old look on a small body. He didn’t speak, just handed her a piece of paper. Marta took it. A single word was written on it: home. And that was enough. Marta hugged him. As she had done with so many others? No questions, no conditions. That night there was hot soup, clean blankets, and a reserved spot by the fire.

Be was on the porch, flashlight in hand. Aris was reading by the window. Milo was playing with the little ones, teaching them how to write their names. And Marta. Marta stood in the doorway for a moment, looking at everything she’d once thought was lost, but she didn’t say anything.

She didn’t need it because what was built there wasn’t just a home, it was something much more difficult: a family. And in a world where many are born without belonging anywhere, she gave them the greatest gift one can give without promising anything: a place to stay, a place to be seen, a place to be loved.

And as night fell once more, the cabin light remained lit for whoever needed it, for whoever arrived broken, for whoever finally returned home. This story isn’t just about a widow; it’s about every woman who gave love when she had nothing, about every child who, even without words, wrote home with their heart.

Để lại một phản hồi